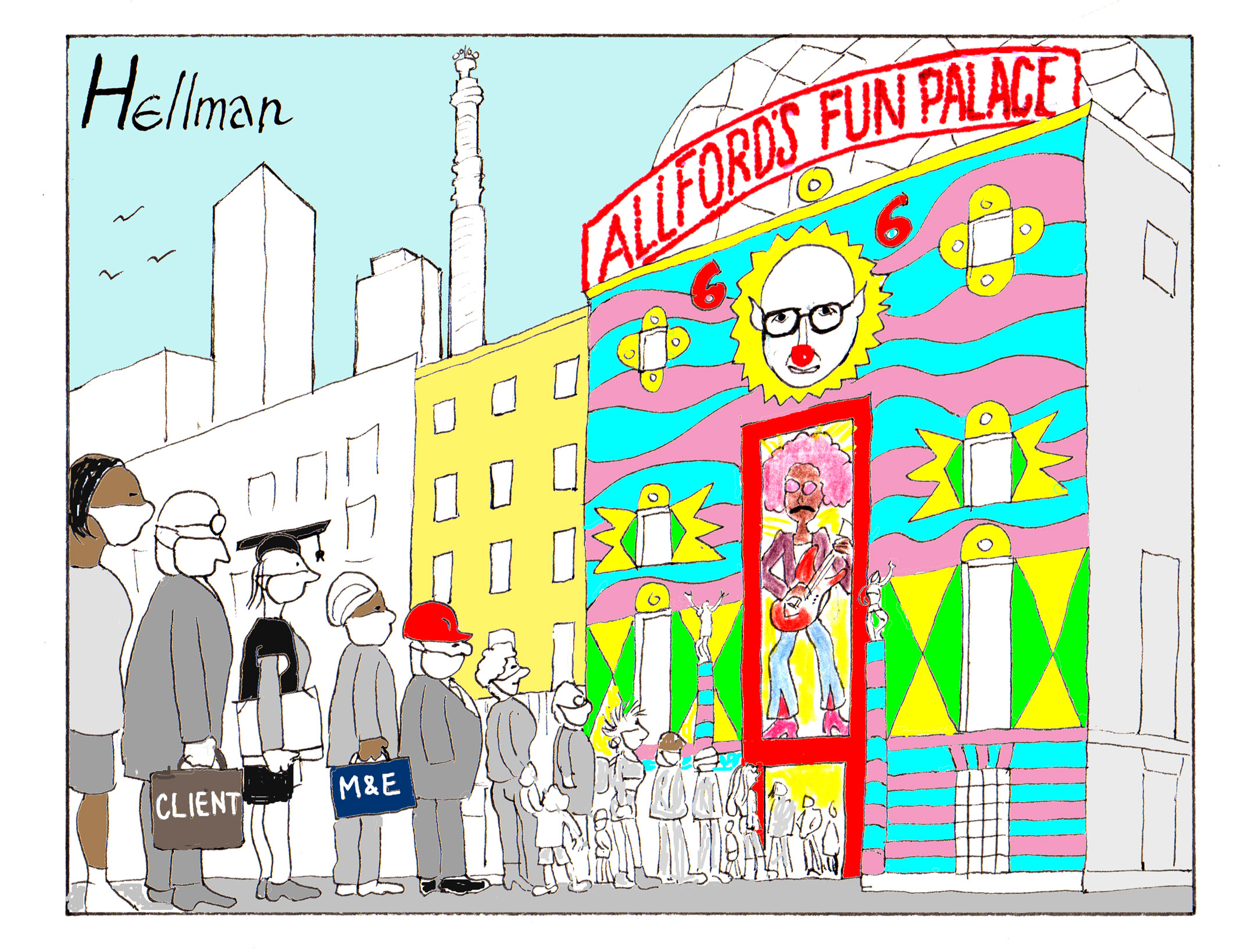

Three years ago, the AHMM co-founder made a stinging attack on the ‘the sadly ever-less relevant’ RIBA, urging the profession to storm its London HQ and ‘take it back for architects and architecture’.

The fallout from this candid swipe at the institute and its new governance structure unexpectedly set the architect on a journey that saw him elected as its 78th president.

He arrived in the post in September 2021, just as the RIBA began laying off staff and started the process of selling off its offices at 76 Portland Place in a bid to tackle an annual budget deficit of almost £8 million.

Advertisement

Set against this backdrop, Allford unrolled big plans to reinvigorate Portland Place as somewhere to experience architecture – rather than just weddings – and create somewhere ‘you can say you’ve seen an exhibition, you’ve been to the library which is open, you’ve engaged in a bookshop, you met someone, you see a talk going on’.

A competition was launched to find an architect to lead the job – dubbed the ‘House of Architecture’ by Allford – which was won by Benedetti Architects in early 2022. But progress on the complex ‘comprehensive refurbishment’ of the RIBA’s 90-year-old George Grey Wornum-designed central London headquarters, originally budgeted at £20 million, has not been speedy.

The project has been made more complicated by the institute’s decision to end a 20-year partnership with the Victoria and Albert Museum, resulting in the RIBA’s artefacts being transferred back over the next five years to join the institute’s existing collections.

In what is thought to be a first, Allford will remain on the board after his two-year tenure ends later this month – in part, to try and see the overhaul through.

As he says: ‘The RIBA has a long history of not quite achieving what it set out to do.’

Advertisement

According to Allford, his successor, 32-year-old Muyiwa Oki, is also expected to back the House of Architecture drive by ‘mapping his Biennial Plan’ on to the existing programme.

So does Allford feel he has been able to effect change at an institute he once, ‘through frustration’, branded an ‘asylum’? And has he left it in a better place than he found it?

Was being RIBA president what you expected it to be?

Yes – for good and bad. The RIBA is an august institute with a long history of not quite achieving what it set out to do. Fundamentally changing the way it operates, given its new constitution and charitable status, has been like trying to change the course of a supertanker. It has been really very difficult. But with a new executive team working under a small focused board that is itself working well with RIBA Council, we have changed course – and completely.

The organisation now better understands its structure, with the board in control of finances and resources, and council keeping a watchful eye on the horizon: engaging through its nimble expert advisory groups on the issues of the day. There is now a focus on what a good institute looks like.

In 2020 you said the profession should ‘storm the building, taking it back for architects and architecture’. Do you think you achieved that?

Yes. Shared ambitions for the House of Architecture are now embedded in the institute’s organisational structure and mindset. And just as crucially, they are embedded in the plans for the institute’s architecture. Architecture has its limits, but as a profession, architects above all must believe it can help define and accommodate a better future.

The House of Architecture establishes a reinvigorated RIBA operating in the virtual and physical worlds as an important outward-looking public cultural institution, both supporting its members and acting as a generous host to discourse: a place where ideas about the design of our low-carbon future are developed and shared – with members, partners, the public and government.

What progress has been made with the House of Architecture proposals – and has it been tricker than you first envisaged?

I always knew it would be tough. But we have a programme, a financial plan, a consultant team and a client team – of which I am a member – all appointed long-term to see the project through. We have had to rethink our attitude to our collections, currently scattered in five locations, and to exit the V&A. We are reinventing both our permanent home, here at 66 Portland Place and its digital twin.

‘The RIBA has a long history of not quite achieving what it set out to do’

Since its inception in 1834, the RIBA has amassed one of the world’s greatest and most complete collections – over 4.4 million photographs, books, journals, artefacts, manuscripts and archives and over a million drawings. Of the 400 Palladio drawings known to exist, courtesy of Lord Burlington, we have 380. This is our defining asset, priceless and of huge value to the profession and society, and a vehicle to connect both.

So we have a great opportunity, which is why we have put in place a sensible and achievable financial plan, safeguarding our endowment, and allowing us to address the years of neglect. We also have a significant responsibility: to look after the remarkable collection our predecessors bequeathed and make sure the collection also represents the best of today.

We can create a historical continuum: our collection will be widely available in analogue and digital format; accessible to all irrespective of means, background, or location; to be used, reused and enjoyed by members, practices, individuals, researchers, communities, students, schoolchildren, businesses and policy and decision-makers.

It is not a coincidence that the last two Royal Gold Medallists both referenced our library and collection as a place and a source of learning. We do this because it is our responsibility and the RIBA then becomes an accessible global research centre.

‘This is not a vanity project; we do not have a choice’

Of equal import is taking responsibility for 66 Portland Place. It is our forever home – well almost, as we have but 910 years left on the lease. The building, as suggested by its Grade II* listing, is a great asset. But its much neglected current condition ill befits its role as home to the architectural profession and our collection.

It is leaky; failing environmentally and acoustically; its services, many original, are decayed and at end of life; its 27 different levels are not accessible to wheelchair users; it has inadequate toilets; limited amenity and an ‘open plan’ fire escape strategy that severely limits its use.

This is not a vanity project; we do not have a choice. Indeed, of all professions, we have a duty to discover and demonstrate what an exemplary net zero reinvention project looks like: what must be done; how it can be best done; and to what great effect we have done it.

The staircase at the RIBA's headquarters at 66 Portland Place

What do you think your biggest achievement has been?

Creating a biennial plan for the House of Architecture@RIBA which has become the longer term plan to which board, council and executive are committed.

What has been the hardest thing to tackle?

When I arrived, architecture had indeed all but disappeared. Council was consumed, board blocked and staff morale was understandably on the floor.

The RIBA was locked in a battle with intransigent forces within. The RIBA was failing – and this failure was, quite unforgivably, instigated by those who were supposed to be leading the institute. Thankfully, three years on, things are very different. Crucially all are now working collaboratively to create a dynamic 21st-century institute of ideas.

Three years ago you branded the RIBA as ‘sadly ever-less relevant’? Do you still think that is the case?

No. I believe the way ahead for the RIBA as the House of Architecture is clear, understood and relevant. Sadly, there will, as Alex Gordon noted more than 50 years ago, always be ‘RIBA’s petty internal squabbles’ but now they will be set against a much clearer long-term vision and plan. Moving forward, with the engagement of members old and new, the remodelled RIBA will play an ever-increasingly vital role in helping us all design that better future and for everybody, since everybody is a citizen of the built environment.

‘Three years on, things are very different’

That said, of course, the RIBA, like any organisation, has to seek to continuously improve both what it offers its members and what it does for wider society. This focus on architectural action is reflected in our updated mission statement: ‘To be the world’s leading centre for excellence in the design of the built environment. Promoting sustainability, building safety, diversity, and inclusion, as we strive for a better future for all communities and the planet’.

Is the institute in a financially more stable place today than it was when you started your term?

Yes. Uncertainty and economic instability have hit hard but also encouraged reflection,which brings to mind the comment of the First Sea Lord in 1917: ‘... we have run out of money. Now we have to think’ ... and we have had to think hard.

The board has stopped the financial rot and we have gone from losing around £7 million a year to moving to breaking even and building the organisational structure that allows for potential future financial growth. We have also protected the NBS monies – which were being massively eroded – in an endowment; reduced our property footprint by selling 76 Portland Place for close to £12 million; and are now sharing Mann Island, Liverpool, in a creative partnership with the Tate.

View of (the now vacated) 76 Portland Place, which was overhauled by Theis + Khan Architects in 2013

How do you plan to ensure that your plans are taken forward and aren’t forgotten about after your term ends?

There is now a focus on both addressing the immediate issues and planning for the long term.

Like all members, I am just passing through. I ended up here because I articulated my frustration. Past president Jack Pringle shared my concern, and together we have worked with the equally committed wider team of council, board, committee members and staff to establish the long-term House of Architecture plan that will enable the RIBA to move to the next level in fulfilling its membership’s needs and its charter commitment.

‘I ended up here because I articulated my frustration’

That plan is in place. So I am both looking forward to stepping down but also to staying on board – literarily and metaphorically – to help the team deliver the House of Architecture. I have often been told that a two-year presidential term is too short. I can assure you that two years plus a year as president-elect laying the foundations is long and feels more than long enough.

Do you need to have a thick hide to be RIBA president?

Yes. Like all institutions, the RIBA attracts some troubled characters from within its membership and they tend to focus on the president. But the vast majority care, contribute and recognise the difference between debate and assault.

The RIBA also attracts criticism from outside, which is inevitable and sometimes justified. When I agree I say so and when I don’t I politely let it go. The RIBA needs to be more confidently engaged and less defensive.

How would you judge the success of the RIBA’s role in tackling the climate crisis and what influence the RIBA Climate Action Group has had in driving that?

With our RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge embraced by the wider industry, we are now leading partners in the next step; and the launch of the NZCBS – another anagram but one that will become more familiar: the Net Zero Carbon Board Standard.

We’ve invested time, money and staff and members’ intelligence in this vital pan-industry tool that will work across client sectors and construction typology to establish a standard for measuring embodied and operational carbon and, crucially, creating potentially a data lake of predicted and actual performance. This tool has global potential.

The NZCBS also happens to be chaired by an RIBA member, David Partridge, who is a leading client. Proof, if ever needed, that architecture is a great training for the world beyond just designing buildings. And a reminder to us that the RIBA needs to better connect to its diaspora – those who have studied architecture and gone on to do other things in related and unrelated fields.

The RIBA must also continue to support, harness and promote the exemplary work of its members – for it is they who can help collaboratively lead the construction industry as it seeks to address the extraordinary challenge of our time. Our new Reinvention Award is an example of just such an initiative.

What advice would you give to the incoming president Muyiwa Oki?

We have met often enough to swap notes. Muyiwa has mapped his Biennial Plan (another initiative we started in my term) on to that which we have pursued and I look forward to him seeing his plans through in his own style.

Muyiwa Oki, the RIBA's 79th president

Do you have any worries about the future of the profession more generally and can the RIBA help with that?

The Climate Challenge is our greatest challenge and focus, and we are beyond declarations. Now is the time for practical action to drive the project that Buckminster Fuller termed the ‘Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth’. But it is also our greatest opportunity. Looking ahead, acknowledging Vitruvius and Alberti, we must pursue a delightful forever architecture; to which nothing need be added; and from which nothing can be taken away – architecture as infrastructure for, and generous host to, the theatre of everyday life.

‘Stronger finances will help reverse our long retreat into an ever more confined role’

But, as a profession, we cannot do what we need to do, without a focus on the commercial drivers of architecture. Yes, architecture drives us. But money fuels both that drive and its construction. Indeed, I know from experience that bad cash flow destroys creativity.

So stronger finances of institute and profession are essential. They will make us more attractive to future generations. They will allow us to reverse our long retreat into an ever more confined role – exploited by others who are willing to take on the challenges that we consider too humdrum, too commercial even!

Moving ahead we must change. We must recognise that money is the constraint that can become the driver of architectural invention (and reinvention) – and of a more confident, capable, and commercially respected profession.

Do you have any regrets about anything you did during your term?

I regret the time I have spent in interminable investigations brought about by a few who see conspiracy everywhere and sadly will never stop. But I also know it has been dealt with and it needed to be done to clear the way for a more constructive and collaborative future. So in a sense no regrets.

What would you most like your RIBA presidency to be remembered for?

The House of Architecture – around which I built my campaign and my tenure – as I firmly believe that a remodelled RIBA can and will play an ever-increasingly vital role in helping us all design that better future, and for everybody, since everybody is a citizen of the built environment.

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.