‘It’s my favourite view,’ says Nick Hayhurst. ‘I like how our building just disappears.’ We’re standing by the Edith Neville Primary School that his practice has designed, staring along its southern boundary. The wide, planted border beside it has grown so exuberantly that from this angle the school appears submerged by it.

The view terminates beyond trees and a scrubby open space at another, less self-effacing building: the distinctive scalloped bedstead-like roof profile of Adam Khan Architects’ mixed-use community hub, which is occupied by the Plot 10 playgroup centre as well as social housing. This, and Hayhurst and Co’s school, are the two thus-far completed elements of the London Borough of Camden’s Community Investment Programme (CIP) in Central Somers Town.

Central Somers Town mixed-use community facility by Adam Khan Architects (photography: David Grandorge)

The neighbourhood, in the south of the borough, sits cut-off and cul-de-sac-like between the respective railway tracks in and out of Euston and St Pancras stations. The area was originally laid out in the 18th century with terraces and squares, but has experienced high levels of deprivation and overcrowding since the railways partially severed it from the surrounding city in the mid-19th century. Today child poverty in the area is running at over 50 per cent and overcrowding is rife. Over a fifth of Somers Town’s population is aged 15 and under. In the past few years new pressures have come from massive development all around it, including Argent’s vast King’s Cross regeneration scheme to the east, where Google’s HQ is still to complete. ‘It’s under siege by wealth on all sides,’ says Edward Jarvis, client design lead on Camden’s CIP team.

Advertisement

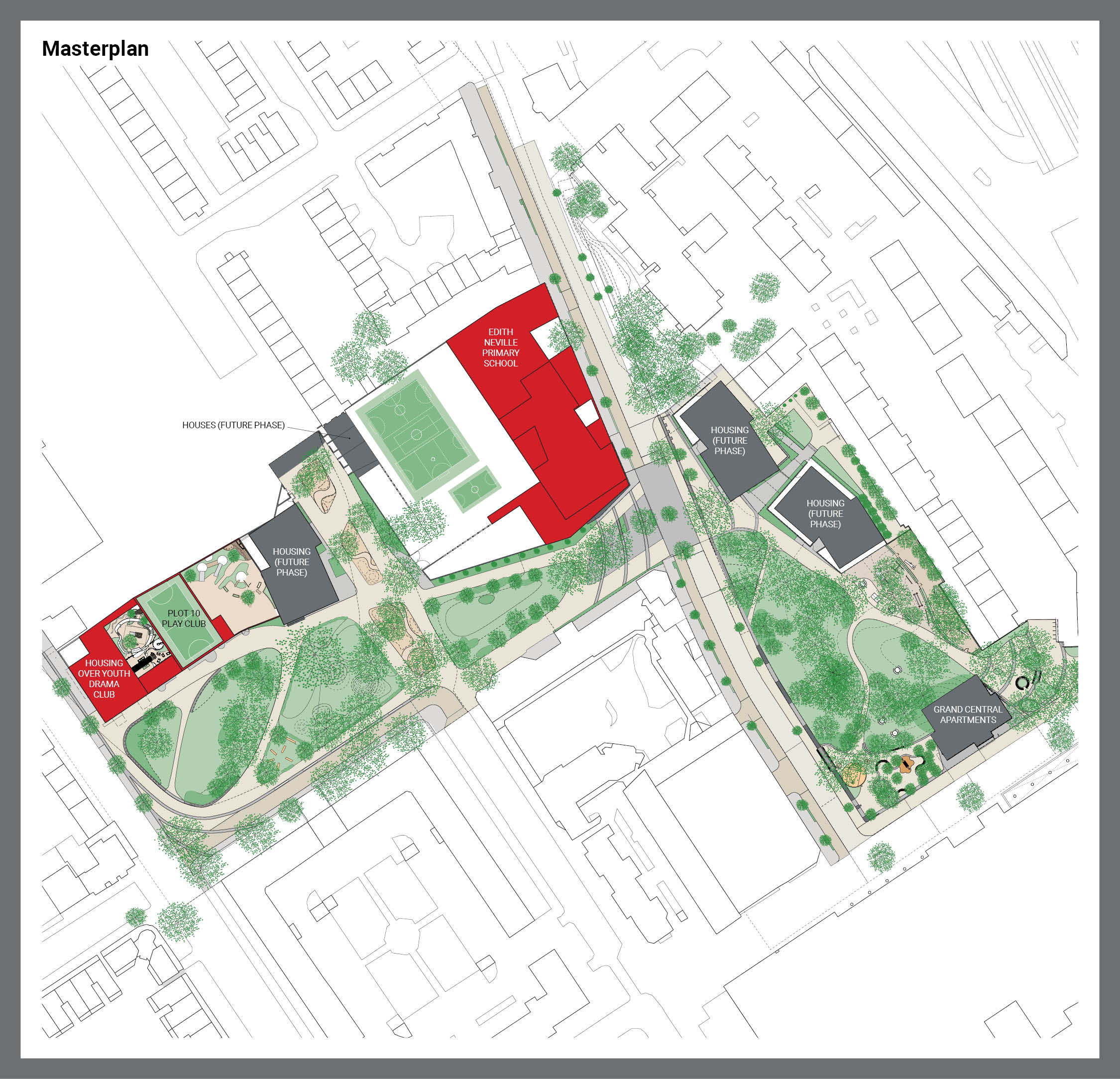

Camden’s CIP schemes are neighbourhood regeneration programmes that focus on the building of new council homes, schools and community spaces. Each is self-funded through the construction and sale of market housing. The Central Somers Town CIP has been masterplanned by DSDHA. In addition to Hayhurst and Co’s school and AKA’s community hub and housing, further social housing blocks incorporating a community space and designed by Duggan Morris (as was) are currently on site. Meanwhile, a 22-storey residential tower – ‘Grand Central Apartments’ – is just completing adjacent to St Pancras. This, redesigned and delivered by Stiff + Trevillion to a consented scheme by dRMM and containing 68 flats costing up to £2.75 million each, is what is paying for the whole lot.

Adam Khan Architects’ mixed-use community facility (photography: David Grandorge)

All the buildings are loosely linked across a fluid series of open spaces, for which DSDHA was also landscape architect. ‘We designed it as a continuous landscape with no straight lines to encourage movement,’ says Deborah Saunt, the practice’s co-founder. Indeed, where we had been standing, contemplating the view to AKA’s hub from Hayhurst and Co’s school, a new connective knuckle of publicly accessible green space has been created after the school agreed to cede a chunk of its playground, allowing a link to be made between two pre-existing green spaces. It’s a move that ensured a crucial commitment could be met to allow no loss of public space in the finished scheme – the new landscaped space compensates in area for that lost to new housing. This new green space superseded a narrow path running between the school fence and the back wall of some housing. It was a pinch point, not well overlooked, that, during extensive consultations with the community was identified – especially by young people – as somewhere unsafe to walk.

On the map, the free-form, open, connective spaces that have been created cut across the area’s relatively orthogonal road grid. The streets, with their predominant north-south axes, are lined by equally orthogonal blocks of 20th century social housing, including the pioneering 1927 Ossulston Estate, inspired by the Karl Marx-Hof housing of ‘Red Vienna’ (Somers Town has been described by Rowan Moore as a ‘universe of public housing ideas’).

Courtyard in Adam Khan's scheme (photography: David Grandorge)

This connective fluidity in the masterplan reflects a similarly fluid and unusually iterative design process (Saunt calls it ‘non-linear’), which dates back to the original appointment of the five practices – DSDHA, Hayhurst and Co, AKA, dRMM and Duggan Morris – in 2014.

‘At that time there was still the ambition to deliver an earlier Nicholas Hare masterplan,’ says Jarvis, himself then newly appointed. ‘But it was a bit dry, more a Georgian repair job, not doing all it could for the community or placemaking.’ Working alongside Mark Hopson, the development consultant who managed the masterplan’s delivery, they explored ways to improve matters. ‘Our idea was to divide the plots up into separate landscape and buildings appointments – using several smaller architects, rather than one big one. Once appointed, they were asked to review and challenge the existing masterplan. We thought more consultation would be useful, too. So we decided to go back a couple of RIBA stages as well.’

Advertisement

‘We expanded DSDHA’s landscaping appointment into masterplanning,’ recalls Hopson. ‘But the review was undertaken collectively by all the architects; hence we ended up with a completely different proposition!’

Masterplan strategy

The London Borough of Camden approached DSDHA to act as masterplanners, landscape architects and spatial strategists, working collaboratively with four other design teams, residents and stakeholders, to facilitate landscape-led rejuvenation of the area in a manner that responds directly to the needs of Central Somers Town. With Camden, we explored innovative models of delivering homes and public amenities through Camden’s Community Investment Programme, a self-funding development framework.

DSDHA did not approach the masterplan – or urban framework as it might be better called – in a traditional, linear way. Rather than developing a set of principles in advance, DSDHA worked concurrently and in collaboration with the other architectural practices. Landscape and public realm were the primary drivers, around which housing and amenities were designed. Through a collaborative and iterative approach in which we developed a sophisticated dialogue with each design team, we were able to provide Somers Town with creative solutions while achieving no net loss of publicly accessible green space.

Deborah Saunt, founding director, DSDHA

Masterplan data

Start on site August 2017

Completion April 2024

Site area 2.2ha

Construction cost £89 million (budget for total Central Somers Town regeneration project)

Masterplan architect DSDHA

Client London Borough of Camden

Structural engineer AKT II

Quantity surveyor Currie & Brown

Project manager Urban Logik

Main contractor Neilcott Construction (plots 1 and 4); Morgan Sindall (plots 5 and 6); Maylim (Purchese Street open space)

CAD software used Vectorworks

Landscape architect Todd Longstaffe-Gowan

Sustainability consultant Atelier Ten

Planning consultant Turley

Lighting consultant Studio Dekka

Transport consultant Civic

Co-design on Purchese Street open space Edit Collective

‘Every week they were moving stuff around,’ says Jarvis. And he points out that every time one plot was tweaked, it could have a knock-on effect on all the others to ensure there would be no loss of publicly accessible space. ‘But the process was amazing and self-balancing. It really felt like doing masterplanning in 3D, rather than just on plan.’ This process was accompanied by six further rounds of community and stakeholder consultation, which included setting up stalls in the neighbourhood’s Chalton Street market. ‘It was really important for finding out what was valuable to the community,’ says Khan, while Hayhurst recalls: ‘We observed the school for several weeks before even putting pencil to paper.’ This resulted in the development of a ‘manifesto’ of shared objectives under headings such as ‘pedagogy’, ‘nature’ and ‘well-being’, which guided the school’s design.

This combination of observation, consultation and negotiation between the community, stakeholders and designers seems core to the genesis of the scheme. It kept all those involved invested in it, not least when major issues had to be negotiated, such as securing the school’s agreement to the reduction of its footprint. ‘It was very important to keep the school on-side,’ says Hayhurst. In the event he delivered a building that has actually increased the area of outside space for children on a smaller plot, through a stacked, terraced design akin to a low-hanging Gardens of Babylon. Another significant change, in answer to local concerns, was the shifting-back of the proposed site of the Plot 10 play group centre to its original position at the centre of the neighbourhood. It was a key move which Khan says transformed the attitudes of local residents, who had previously been ‘grumpy’ about the proposals. Plot 10 offers wrap-around care for the children of working parents from reception to Year 7. Founded by local parents in 1973 on a still-undeveloped bombsite (indicative of the area’s long-term neglect) it has remained a backbone organisation in the community ever since.

One of the spaces in Adam Khan's scheme (photography: David Grandorge)

Shifts of remit and responsibility occurred between plots and designers, too, with Hayhurst taking on the design of a short run of terraced housing sitting alongside the boundary of the school, which had originally been assigned to Duggan Morris. ‘It was an unusual way to go about things, but it led to such an amazing and genuinely fluid process that allowed both community engagement and peer review to be effective,’ says Jarvis: ‘It’s hard now to see which decisions were chicken and which were egg.’

But, with so many moving parts, the project has taken a long time to realise, not helped by the pandemic – nor by certain contractual issues, which delayed the handover of Plot 10’s building.

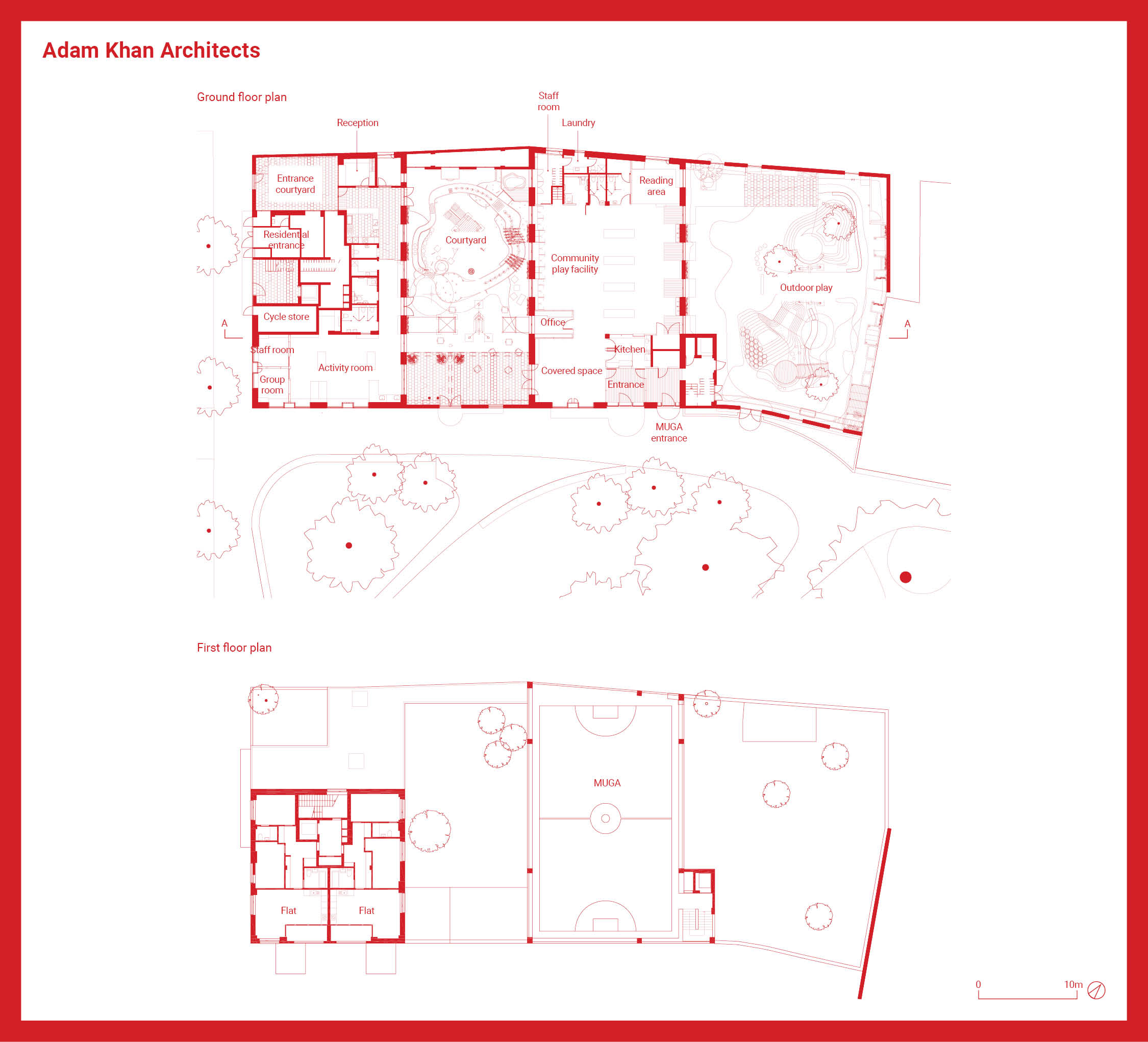

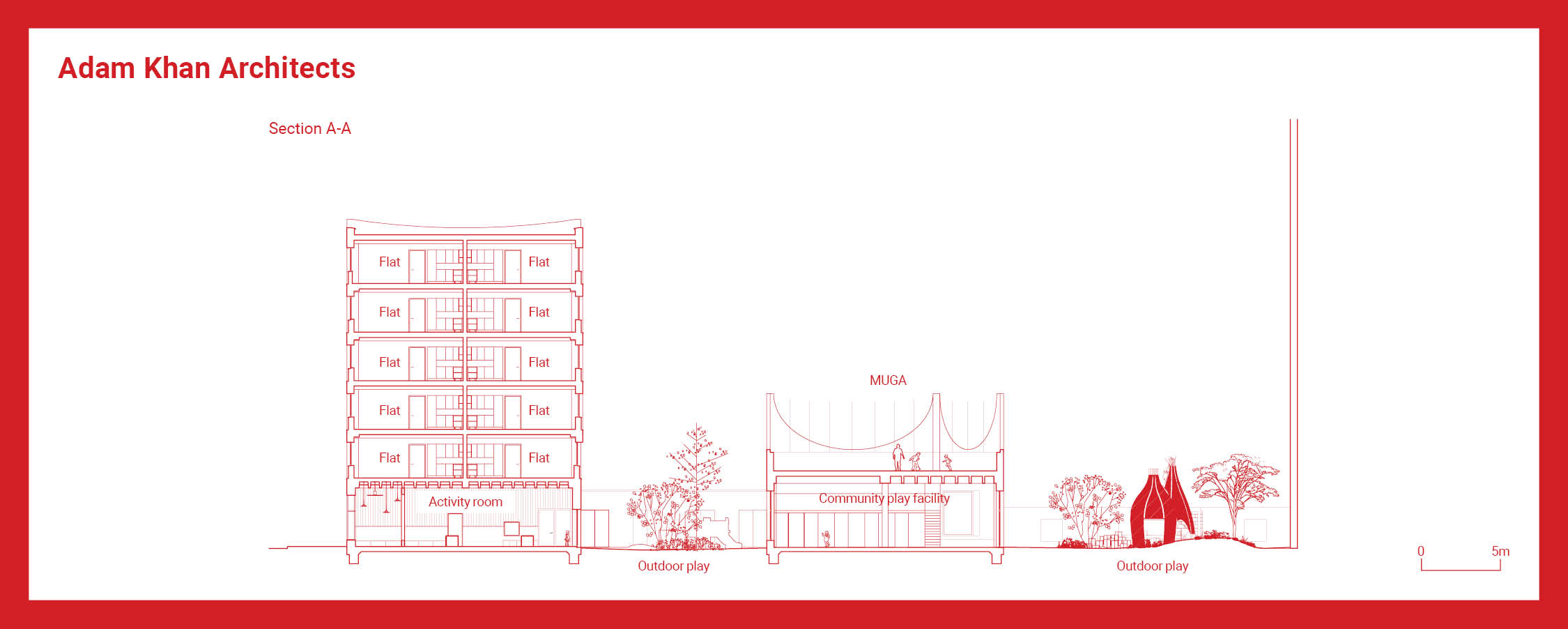

With DSDHA’s landscaping still to go on site the central square-like space bordered by Chalton Street and Polygon Road is for now still composed of the scrubby patches of grass and fenced-off areas typical of municipal plots. But it already has a more focused, urbane and civic-centred feel to it, being faced now on the east by the school and its oversized portal, fronting a playground (‘I wanted to celebrate and emphasise the kids’ entrance,’ says Hayhurst). To the north side are the arcaded entrances and openings of Plot 10 and its associated six-storey housing block, with generous balconies projecting overhead. Khan describes its distinctive profile both as ‘a little civic institution’ and ‘a small palazzo’.

Rooftop play (photography: Lewis Khan)

It certainly amplifies the echo this small public space has – close to but removed from the buzz of St Pancras and the Euston Road – of one of those quiet, out-of-the-way piazzas in Venice that sit just off a packed tourist route. The architecture and buildings lining such places impart a sense of local civic-centredness: a church, a small palazzo or, as here, a school, activate and bring the place alive through waves of activity each day, be it, as on the afternoon of our visit, an impromptu martial arts class, or parents chatting around the school gate, waiting for the end of lessons. DSDHA’s proposed landscape design bodes well, informed as it is in part through a process of co-design workshops that Edit Collective held with local teenagers. The layouts are loosely orchestrated, with paths, benches and changes of surface, as well as open areas of green. It’s a light-touch activation of public space that offers suggestions, not proscriptions for its use – an approach similar to what Jeremy Till has termed ‘slack space’.

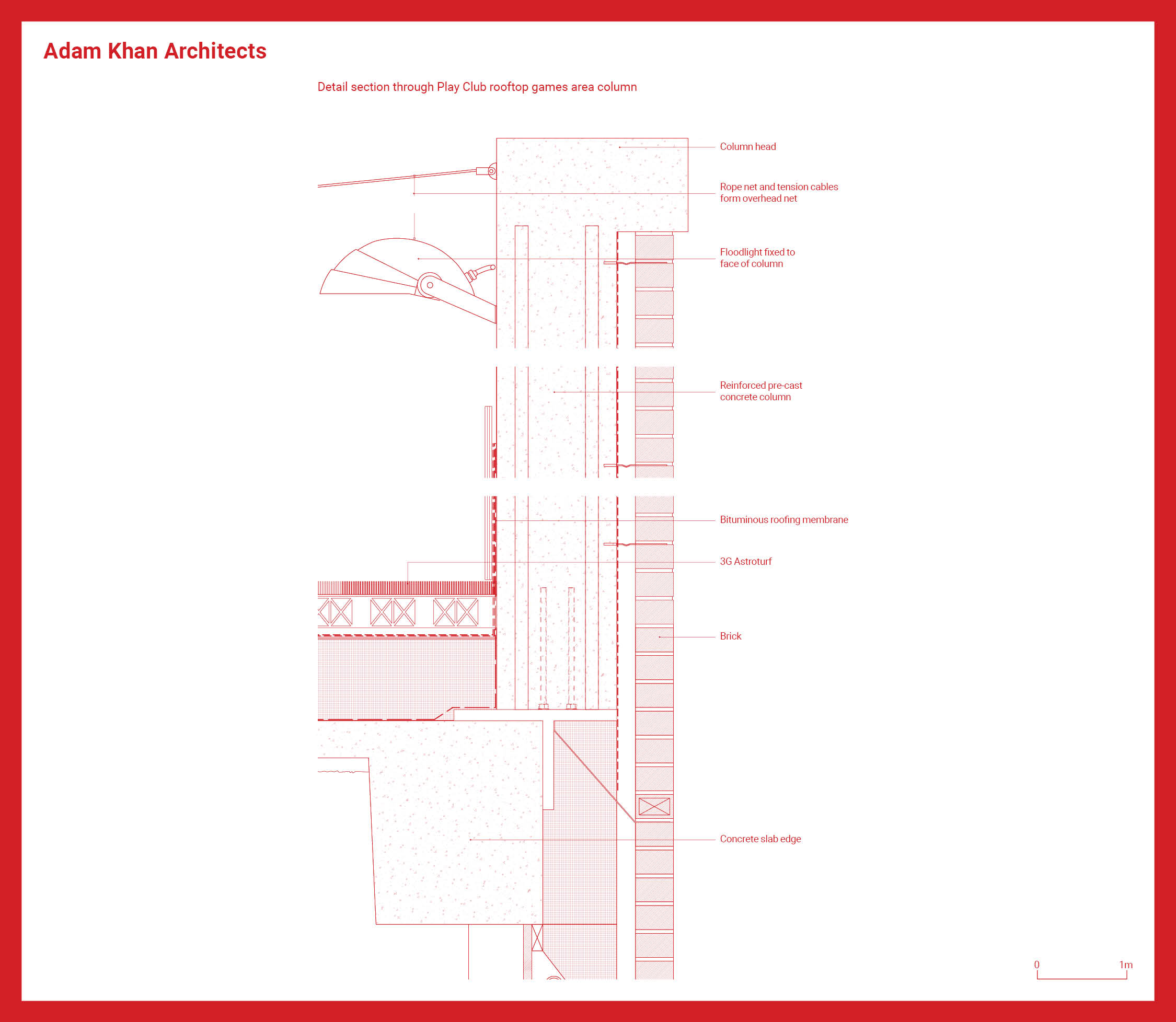

Khan describes the scalloped roof profile of the Plot 10 building, which is echoed in the gentler scooped parapet of the adjacent six-storey housing block, as a ‘celebratory crown in the neighbourhood’. This ‘crown’ has a practical purpose, enclosing a rooftop five-a-side-type sports pitch and multi-use games area (MUGA) – nicely enshrining outdoor activity as a crowning purpose in an area where many youngsters live in overcrowded flats with no outside space.

Edith Neville Primary School (photography: Kilian O’Sullivan)

The buildings are clad in flecked Fletton brick. ‘It’s the sort of brick you usually associate with the back of cinemas!’ laughs Khan. ‘I love its texture.’ In plan they describe what Khan calls ‘a kind of figure or ground’, the two blocks in counterpoint to two enclosed courtyards, one originally intended as a nursery school playground and the other more an adventure playground for Plot 10, lined with meaty timber play structures. In all, the buildings feel both topped and tailed by the copious play spaces, each wrapped by boundary walls with inverted-arch cut-outs. These allow glimpses through while conveying a castellated feel, expressive of the balance between connection to and security from the wider surrounding city. ‘Kids love it. They are free to run around in the open air and feel safe,’ observes Sally Warren, Plot 10’s manager.

Foyer of school (photography: Kilian O’Sullivan)

Behind the façades, there’s a looseness and generosity to the internal spaces, balanced by tailored areas for more focused activities. This echoes the arrangement of the public spaces outside. A single lofty space almost completely occupies the footprint of Plot 10’s ground floor. It’s straightforwardly structured under exposed concrete beams, offering good thermal mass. Built-in secondary structures of Douglas fir and glazed partitioning form offices and storage mezzanines and other corners are kitted out as a kitchen or reading spaces. There are good light levels and the massive, wall-high, openable glazing allows cross-ventilation from courtyard to courtyard. This flexibility of internal layout has meant that spaces originally designed for a nursery school on the ground floor of the housing block pivoted easily to accommodate a youth drama club. Display windows designed for toddlers’ work now showcase wonderful theatre masks instead.

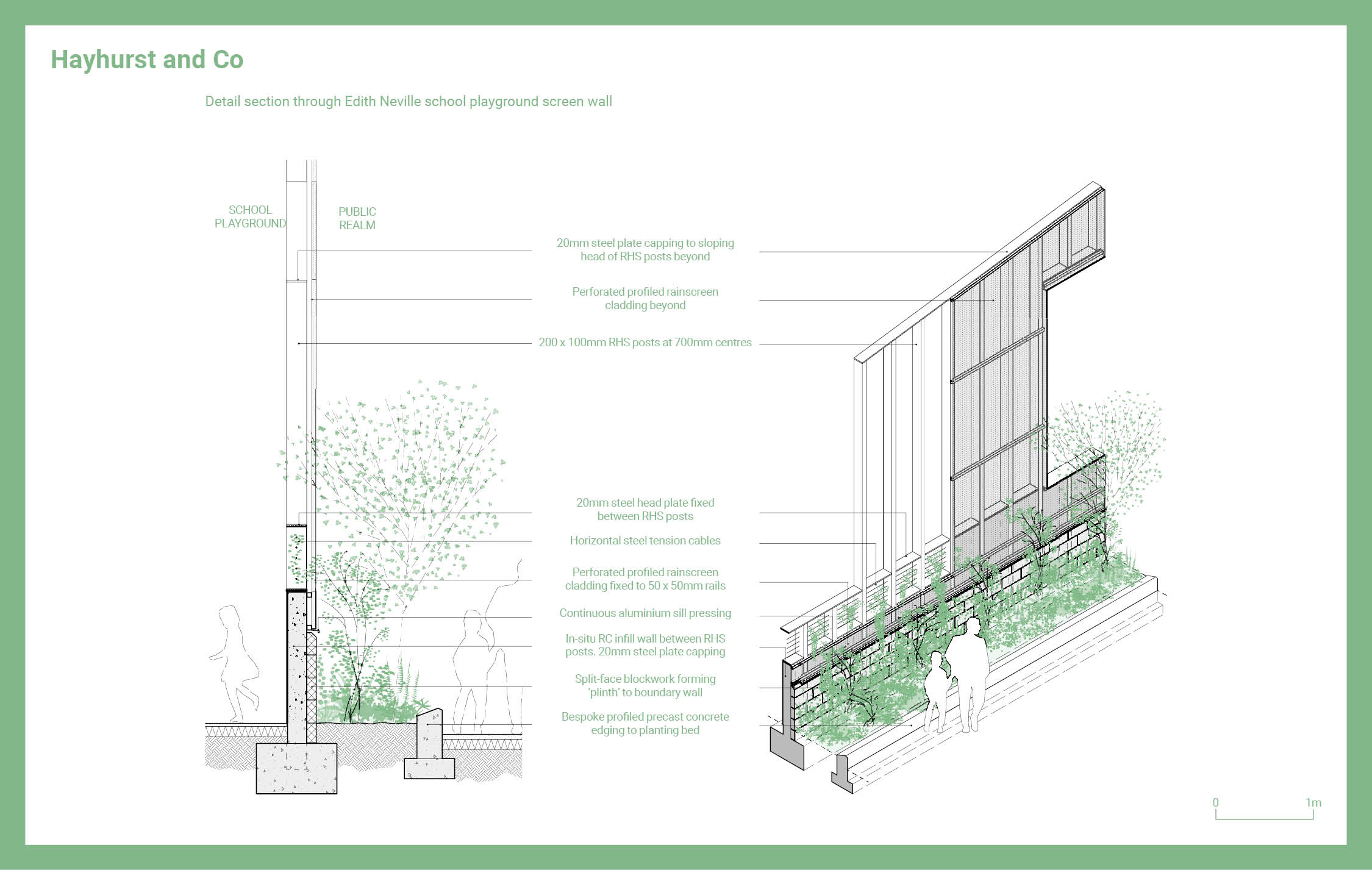

The school makes a similar play of generosity, openness and light in its design, but with a contrasting soft palette of creamy brick. It sits set back on its site across a playground that appears to be an extension of the central square. This illusion is down to the careful calibration of its screen wall: its tall steel staves and tension cables feel permeable and non-exclusionary from the outside but appropriately secure and embracing seen from inside at a child’s height.

Hall of Edith Neville (photography: Kilian O'Sullivan)

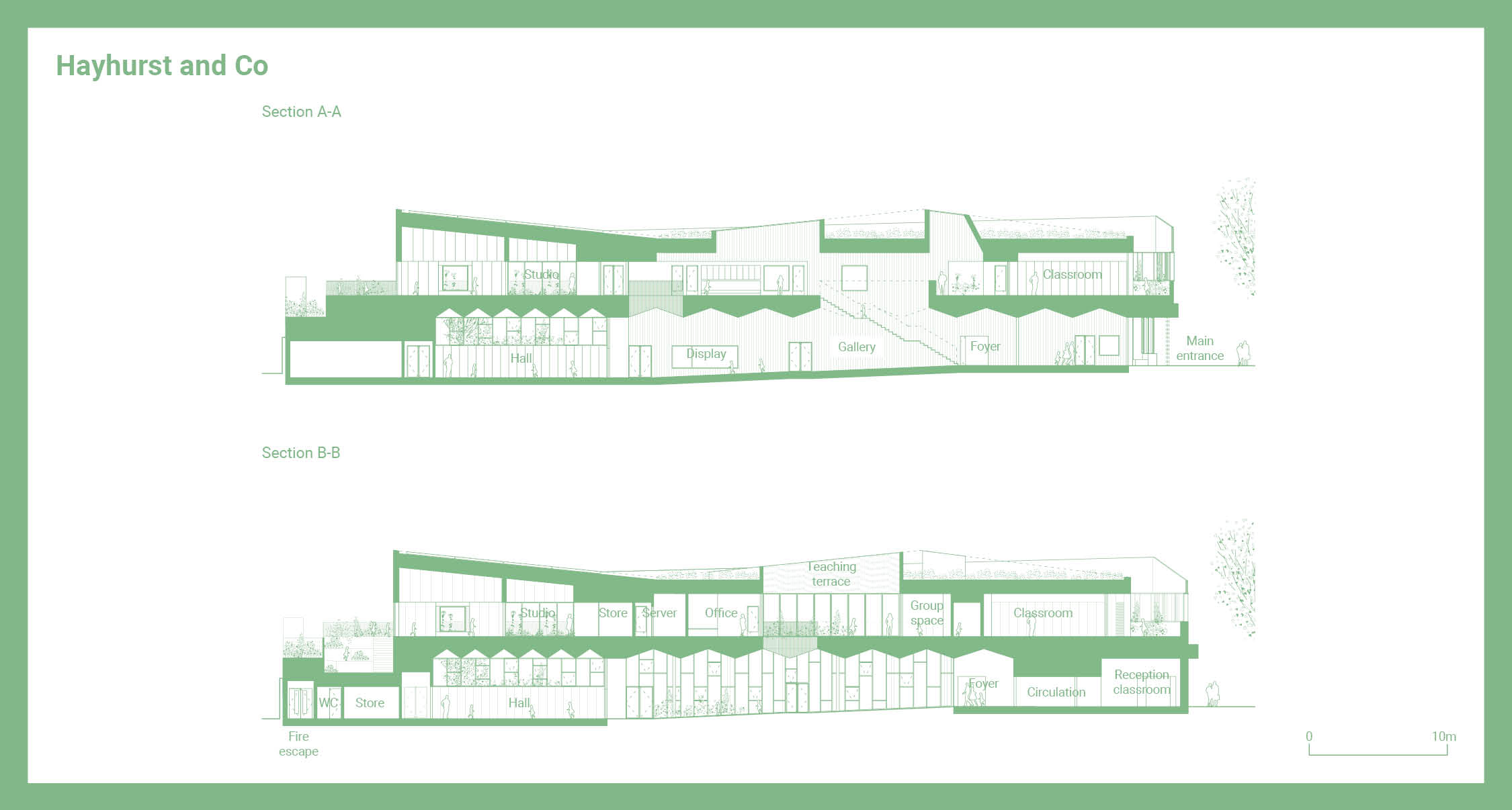

The main building, primarily a CLT structure, is self-effacing, given its relative size, being low-slung and faced by two storeys of stacked terraces. ‘The strength of this building is its weakness,’ says Hayhurst. ‘It's meant to be weak – a background, more about space than elevations.’ Internally, a main ‘gallery’ space banks down to a school hall. With a wide main stair, it has a soft, landscaped feeling and doubles as central circulation and exhibition space. The slope of its floor neatly enables the taller hall volume to be accommodated under a single, platform-like first-floor plate. This upper level, lit by copious skylights, is lined by classrooms, each with its own small display window adjacent to its entrance, displaying each class’s work.

In a neighbourhood defined and blighted by hard borders of rail and road, the intelligent calibration of boundaries in this scheme, balancing enclosure and security with visual interest and permeability, means the new buildings engage with their immediate surroundings. This, combined with a generous provision and gradation of public space that’s thoughtful but not over-determined, bodes well in offering a real improvement to Somers Town, reinforcing its sense of community.

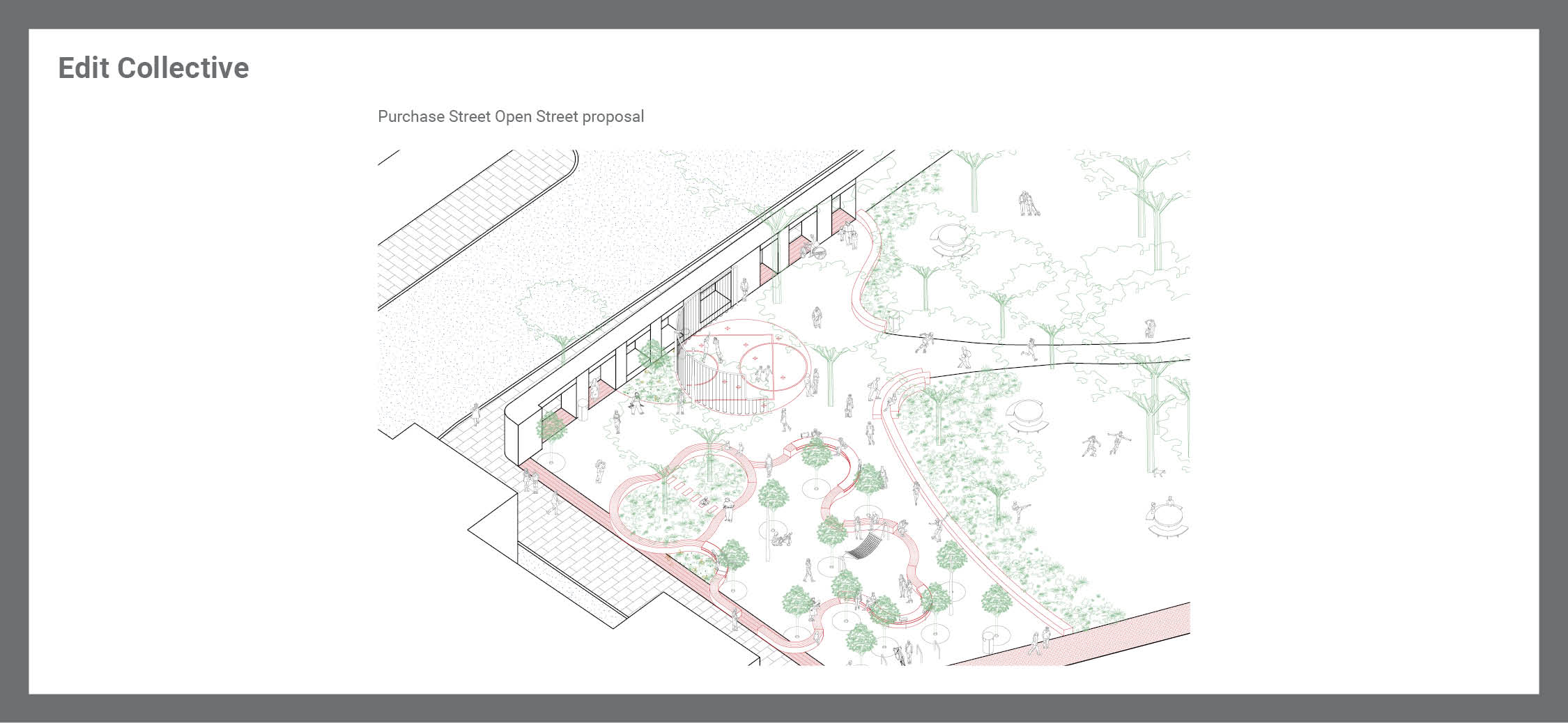

Co-design with Edit Collective

A long-term community engagement approach, punctuated by focused periods of co-design, has underpinned the development of the landscape masterplan for Central Somers Town.

The proposal includes a diverse range of play and social spaces, suited to different user groups and their needs, which were uncovered through the initial community engagement process. The detailed design of the activity and social space to the south-west of Purchese Street on the site of a former enclosed multi-use games area, was developed through a co-design process in collaboration with the Edit Collective and a group of young people from Somers Town Community Association Youth Club.

Edit organised a series of workshops, using the association’s centre on Ossulston Street as a meeting and workspace. The sessions included site mapping and analysis, brief writing and concept design, and development of detailed proposals for materials and finishes, together with local young people.

The final workshop included a design review with STCA, Edit, DSDHA and the London Borough of Camden client team, with 1:1 testing of the site layout design to ensure all participants were in agreement on the outcome of the co-design process.

The co-design process for the Purchese Street Open Space highlighted a desire for three zones that transition across the site from intimate, through sociable, to playful areas. The participants wanted to create social and comfortable places to sit with friends, with a mix of seating arrangements and types for different group sizes.

Early site analysis and design discussions centred around making spaces that feel safe and comfortable for different users, considering women and girls, children of different ages, older people, and people with disabilities. Participants expressed a preference for a muted and natural palette, rather than bright and often overpowering colours, to complement the existing material surroundings and neighbouring spaces.

The priorities of the young people included a hammock seat for informal lounging in a quieter part of the site, and a basketball hoop in the more sociable and busy entrance area. The sloped surfaces of the new curved seating allow for incidental play and enjoyment of the space by younger children visiting the social space, ensuring a mix of alternative play spaces are provided for a range of ages and abilities.

Anne Wynne, associate, DSDHA

Architects’ view

Plot 10 is a club offering childcare for four to 11-year-olds every day before and after school and during the holidays, providing a lifeline to working parents. Set up by residents in the 1970s, Plot 10 is a rock in the community.

The play club and youth drama club are laid out along a public park as an enfilade of courts and rooms, held together by a unifying celebratory façade, like an 18th century château or hôtel particulier. We like the directness of the façade sitting right on the public realm, with a precisely tuned threshold. A strong hierarchy of openings, glimpses into courtyards and deep window reveals quietly satisfy the many and stringent safeguarding and privacy demands, while projecting welcome and vitality.

Swooping inverted arches enclose a rooftop sports pitch. The motif is familiar from London garden walls but amplified to give a larger scale of representation across the park. They subsume the sports elements into an overall singular façade and achieve a distortion of scale – a grandeur at odds with real size, like a child’s model of a palace. The small tower of housing affirms the scale of the street while maintaining this delicate quality.

The interiors further develop this play of scale. The rooms are tall, of exposed concrete and lined with large windows. These robust shells are fitted with Douglas fir-glazed partitions in an evident layering, like a factory, creating functional rooms and structuring the open volume to create defined nooks. Linings and furniture are combined, using the same Douglas fir to bring intimacy and softness. The matrix of courtyards and rooms gives a rich porosity, flexibility of use and natural ventilation. Adam Khan, director, Adam Khan Architects

Client’s view

Central Somers Town is part of Camden’s ambitious Community Investment Programme, which is investing £1 billion into our communities. It is our way of providing new council homes –to over 1,000 residents to date. We are building some of the most energy-efficient homes in the UK, as well as new school buildings and new community centres, despite significant cuts in the funding that we receive from central government.

Central Somers Town is an excellent example of everything the programme is designed to achieve for our residents. The scheme is delivering 44 new, high-quality social homes, a state-of-the-art school and play facilities, as well as a new community centre and sports facilities.

The scheme is underpinned by key principles developed together with the local community: increasing the number of social and affordable homes; building homes that are larger and more sustainable; generating funding for a new school building; and creating a more connected estate with no loss of public or green spaces.

We took an innovative, flexible approach to the masterplan. We worked together with five architects, rather than one, so that it could continually be reshaped and developed in response to ideas coming forward from both the architects and our residents.

For example, the final masterplan placed the school right at the centre of the community, set back from its original boundary so as to connect two previously disjointed, poorly planned public spaces into one reimagined area.

The decision not to fix the masterplan before designing individual buildings created an entirely new look and feel for the spaces and the buildings. It defined the project and transformed Central Somers Town into a place that has genuinely been reimagined with – and for – the residents.

Councillor Danny Beales, Camden cabinet member

Environmental design

The buildings have exceptional passive cooling features. The windows are not too big and use solar control glazing to provide good daylight without excessive solar heat gain. For the apartments, further solar control is provided by movable external shutter shading. The window openings are large and arranged on at least two different sides of rooms in living areas, providing cross-ventilation.

The building is constructed from dense concrete blockwork with wet-applied dense plaster, rather than cheaper lightweight plasterboard walls. This provides lots of thermal mass, which is used in conjunction with night-time ventilation cooling via window and vent openings.

The total site energy use, including an estimate for the district heating network efficiency, is 136 kWh/m2/yr. This can be compared with the 2020 Energy Use Intensity (EUI) target set out in the RIBA Climate Challenge Version 1 (2019, a year after this project began on site). This gives 170 and 105 kWh/m2/yr for non-domestic and domestic buildings. An area-weighted average of these provides a composite target of 135 kWh/m2/yr for this project – the same as the measured performance. EUIs measured at tenancies are much better. The building energy performance is let down by the district heating system mandated by planning. However, this does demonstrate that the building fabric, heat recovery and low-use hot water system’s efficiencies are good. Heat emitters are designed to operate at low temperatures to allow for future conversion to heat pumps. If, in the future, the district heat network is changed to being supplied by community heat pumps at COP of 2.5, the predicted site EUI is 66 kWh/m2/yr, comparable with the RIBA CC Version 2 (2021) 2030 target of 60 kWh/m2/yr for schools.

Hareth Pochee, principal engineer, Max Fordham

Architect’s view

The school design is based on a shared ‘manifesto’ that evolved from the detailed conversations we undertook with the school community and the local authority. This established the project’s key objectives and a vision for the identity of the educational environment and covered subjects such as ‘pedagogy’, ‘nature’, ‘community’ and ‘well-being’: defining and expressing the school’s ethos and community outlook.

The school is pivotal to the Central Somers Town community, allowing essential social interaction for many parents and providing the opportunity for the school to engage with the wider family unit. The design of the new building was therefore developed around the idea of a family-scale courtyard, an ‘oasis’ that welcomes families into the heart of the school site and into the internal ‘gallery’.

The ‘gallery’ is formed from the main route between the entrance and the hall: a space for large-scale artwork, exhibitions and to encourage parents to mingle in the heart of the building. It also defines the visual character of the school as a mature civic building that acts as a backdrop to the children’s activities. Similarly, classroom storage walls are punctured to create ‘shopfront windows’ for each class to present their work. Windows and rooflights mediate long and short views to make teaching spaces feel a part of the extended landscape and wider city.

Nick Hayhurst, director, Hayhurst and Co

Client’s view

Our new school building has given us the chance to provide a range of opportunities for our children. We have been able to expand provision for art, music, drama and cooking in our studio, a flexible teaching space which allows for creative activities to happen away from the children’s usual classrooms. Gallery spaces allow us to showcase the children’s work effectively, which gives them a sense of pride in their accomplishments. The school hall was designed to be a large performing space and can also be converted into two more intimate spaces. This flexibility ensures we can tailor the space to meet the needs of different groups.

Somers Town is an area of high disadvantage and many of our children live in overcrowded housing. Our new building was designed to ensure the children have access to space and natural light. This has brought a feeling of calm across the school and has supported the children’s wellbeing. The wider area also lacks safe spaces to play outdoors. Our playground has ensured children have access to safe running space and also spaces to be outside where they can engage in quiet activities.

The terraces outside each classroom provide further outside learning space and have also enabled us to teach gardening skills. These spaces allow children to enjoy ownership over their class planters and are an important part of our mental health provision. Dedicated spaces in the playground also allow for nurture groups to take place with a gardening focus.

Ruby Nasser, headteacher, Edith Neville Primary School

Working detail

Fronting the street on three of its four elevations, the school’s boundary was conceived as a permeable and planted backdrop to the masterplan’s new public realm.

The boundary comprises rough-faced blockwork, super-sized steel posts, wire tension cable and filligree, profiled aluminium sheeting, which continue around building envelope and external spaces alike. Each material stops and starts, steps up and down, is layered or punched-though to suit the specific requirements of the boundary at any given point – be that for cladding, edge protection, visual screening, or a framework for planting.

At its base, the split-face blockwork forms a weighty ‘plinth’, providing a robust barrier to the pavement – a language shared with the masterplan’s other buildings. Behind and through this, end-on RHS posts, 700mm apart, slope in height from single-storey on the western corner to two and a half storeys over the main entrance. This traced delineation of the site edge is a direct reference to the courtyard housing typology of the surrounding Somers Town blocks, as well as a device to increase the school’s scale amid its impending, taller neighbours.

This detail illustrates a moment in the boundary to the southern elevation where elements have been layered and peeled away above the plinth, to allow the public space to visually continue through it, blurring the park’s edge whilst still creating a secure school play space. The boundary’s final material is planting, which will grow in-front of, onto, through and behind the structure, further imbedding it in the park.

Jamie Wakeford Holder, project architect, Hayhurst & Co

Edith Neville (photography: Kilian O'Sullivan)

Project data

Central Somers Town Community Facilities

Start on site December 2017

Completion November 2021

Gross internal floor area 1,733m2

Construction cost £10 million

Construction cost per m2 £5,770

Architect Adam Khan Architects

Client London Borough of Camden

Structural engineer Price & Myers

M&E consultant Max Fordham

Quantity surveyor Sweett

Project management Urban Logik

Principal designer Currie & Brown

Acoustic, sustainability and environmental engineer Max Fordham

Landscape architect Jonathan Cook Landscape Architects (RIBA stages 4-6), LUC Landscape Architects (RIBA stages 0-3)

Planning consultant Turley

Cost consultant Currie & Brown

Main contractor Neilcott Construction

CAD software used Vectorworks

Edith Neville Primary School

Start on site November 2017

Completion January 2022

Gross internal floor area 2,125m2

Construction cost Undisclosed

Architect Hayhurst and Co

Client London Borough of Camden

Structural engineer Price & Myers

M&E consultant Max Fordham

Quantity surveyor Currie & Brown

Project management Urban Logik

Principal designer Currie & Brown

Approved building inspector London Borough of Camden

CAD software use Revit, Vectorworks

Environmental consultant Max Fordham

Civil engineer Price & Myers

Acoustic engineer Max Fordham

Fire engineer Warringtonfire

Landscape designer Howard Miller Design

Masterplanner DSDHA

BREEAM consultant Currie & Brown

Employers agent Capital

Planning consultant Turley

Client design adviser Fluent Architecture

Main contractor Neilcott Construction

Annual CO2 emissions 7.9 kgCO2/m2 (annual BER calculated. Estimated 35% improvement over Building Regulation targets)

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.