On Rivington Street in the thick of Shoreditch, known for its night clubs, pop-ups, even a Banksy, and for being one of London’s first ‘ultra-low emission thoroughfares’, sits the Black & White Building. At 17.8m it is central London’s tallest mass timber office building, and has been designed by timber specialist Waugh Thistleton Architects for workspace provider The Office Group (TOG).

It sits opposite 81 Rivington Street, a 1930s Art Deco building retrofitted as an office and co-working space and also owned by TOG.

The Black & White Building recently made headlines for being a case study of a ‘boundary-pushing sustainable workspace’. So, what makes it so special? Despite being the first workspace to be built from the ground up by TOG, which has spent almost 20 years retrofitting existing buildings, it is powered by 100 per cent renewable energy sources (including 80 PVs on its rooftop) and has over a third less embodied carbon than comparable six-storey structures due to its (mostly) mass-timber construction. It is also designed to be taken apart and re-used elsewhere in the future. This carbon saving amounts to 1,083 tCO2e – equivalent to 4,335 hours of flying in a Boeing 737-400.

Advertisement

Source: Jake Curtis

The building takes its name from the former timber seasoning shed it has replaced. This was refurbished into a workspace in 2013 by Buckley Gray Yeoman, which painted it black on the outside and white on the inside, a simple, monochrome move appropriate to its Shoreditch ‘arty’ clientele.

The original building was a traditional warehouse remnant of Shoreditch’s making industry, with a brick structure, large windows, high ceilings and massive timber beams. It seems a shame it was knocked down to build new but the tight site, lack of strong foundations and high value land made it unviable for extension. As an alternative, TOG’s co-founders Olly Olsen and Charlie Green set out to create the most sustainable new building they could.

Waugh Thistleton seemed the obvious choice to design the replacement. The practice is well known for being a long-standing advocate of timber as a sustainable alternative to conventional building materials – pushing hard for this despite challenges in terms of post-Grenfell fire regulations and insurance demands.

Source: Ed Reeve

It has been responsible for pioneering timber residential blocks Dalston Works and Murray Grove, although more recently it has worked more in America and Europe, a reaction to the UK’s stringent building regulations relating to timber.

The Black & White Building makes the most of Waugh Thistleton’s experience and research. Its structure from the ground up is formed of a cross-laminated timber (CLT) core in conjunction with a laminated veneer lumber (LVL) frame. Both are high-performing engineered wooden materials that minimise carbon in both construction and operation. Glulam has been used for the curtain walling while the columns and beams are of beech LVL. The project used a total of 1,330m3 of timber, amounting to 1,774 trees harvested from certified forests in Austria and Germany. Apparently for a typical sustainable forest to regenerate the quantity of wood used in this building would take approximately 137 minutes.

Advertisement

The streetside exterior is clad in timber louvres, crafted from a thermally modified Tulipwood recommended by the American Hardwood Export Council and supplied by Northland Forest Products. These run from street level to the roof and aim to provide natural shade, reducing solar gain on the façade while boosting the reach of light to the interior. They alter in depth as they ascend the building, carefully calculated to optimise efficiency and minimise the amount of solar coating required to protect the clear glass windows. Although supplied from overseas, this timber is highly affordable, lightweight, readily replenished and thus has minimal environmental impact. Its use here (the first time in the UK as a fire treatment and on a multistorey building) highlights its potential for future applications.

Source: Jake Curtis and Ed Reeve

If I was going to be nitpicky, I would say the façade fins could be slightly more filigreed and their intervals reduced to obscure the wall of glazing even more and help lessen the mass of the building on the street. But they’re aesthetically polite with their reddish colour complementing the brickwork of the surrounding buildings. And at night, from the outside looking into the illuminated ground floor, there’s lots to be jealous about in this workspace.

Its interiors have been designed by Daytrip – a studio often featured on The Modern House –and continue the theme of natural materials across the entire scheme, consisting of exposed timbers and natural textiles. ‘It’s good for companies because people working in timber buildings tend to stay in the job longer,’ says Waugh Thistleton director Andrew Waugh. ‘They feel happier and they’re more productive.’ There are bespoke armchairs by Sebastian Cox in the ground floor lounge, and modular sofas by Kusheda Mensah, whose designs aim to combat stress and anxiety in a world powered by social media. A highlight is the oak end grain block flooring across the ground floor – a lovely contemporary detail subtly contrasting with the exposed timber structure.

Source: Ed Reeve

Along with its materiality, the building’s interior is legible and perhaps typical of the ‘hipster’ workspace one would find elsewhere in TOG’s portfolio. Throughout, there are generous lounges of varying sizes and layouts, as well as lots of break-out areas and pockets of outdoor space (you can see Theis + Khan’s 2010 Stirling-nominated high-end resi scheme Bateman’s Row from one – rumour has it that a well-known celebrity has snapped up the top floor flat).

A lightwell runs the full height of the building from the rooftop terrace down to a courtyard containing a single maple tree on the lower ground floor – a sensible way of dealing with the incredibly deep floorplates. Unfortunately for the scheme’s sustainability credentials, the basement had to be built out of concrete, accounting for much of the building’s carbon cost.

Altogether, the building is home to 28 offices, six meeting rooms, two event spaces and 94 bike storage spaces. On the lower ground floor, beside the indoor courtyard and open to the sunlight, is a yoga studio to aid mental wellbeing. Every internal space is clearly functional and, as Waugh Thistleton describes it, ‘visibly sustainable’. Although not a knockout architecturally, the building’s impact is in its clear sustainable readability, making it appealing to architects and non-industry professionals alike. Its extensive use of timber is certainly optimistic.

Source: Jake Curtis

At the building’s launch in January, TOG’s Green dug in on the aspect of social connection underpinning the design of the scheme. This is an obvious concept for new workplace schemes, especially in a post-pandemic world. The sheer amount of bespoke timber in a spectrum of tones and finishes softens the slickness of the spaces through its tactility. It gives a definite warmth and conviviality to what is a fairly large mass on a tight plot in Shoreditch.

What has added a social significance to the story, however, is the introduction of a mentorship programme when it came to its furnishings. A year ago, TOG’s head of design Nasim Köerting approached Power Out of Restriction (POoR) Collective, a social enterprise that focuses on the development of communities through the elevation of young people.

The collective was founded by Shawn Adams, Matt Harvey, Larry Botchway and Ben Spry when they met at the RCA, and at the time they had just completed their Build The Way programme, in which they teamed up with architecture practice GPAD to facilitate an internship for a university student (they completed crowdfunding for the second iteration last year). ‘We had done a lot of workshops and one-off activities and events,’ says Adams, ‘but we wanted to do something long term and a bit more substantial.’

Source: Jake Curtis

Köerting wanted to champion young designers. And she wanted to create an opportunity for a programme to take place at TOG’s new flagship building. After some back and forth with POoR, the idea developed for a possible art piece or tangible output celebrated in the building. It made sense that this would be made by young people collaborating with some of the designers already lined up to make sustainable furniture pieces. As a result, a Makers & Mentors design-mentorship was conceived.

‘We wanted to collaborate with TOG,’ says Adams, ‘because they see the power of young creative minds but also want to provide students with genuine design opportunities. Working with TOG, we hope to kickstart the careers of emerging talent.’

The programme lasted six weeks and, from a shortlist of nine design students from all over the UK in their second and third years of study, three students were matched with three London-based designers to develop a piece of furniture, accessory or artwork for permanent installation in the building, with an emphasis on sustainable materials and social connectivity.

Source: Jake Curtis

Left to right: TOG co-founder Charlie Green and POoR Collective founding partner Shawn Adams; Sebastian Cox with Isobel Browne-Wilkinson; Andu Masebo with Emilie-Gabrielle Lemaitre- Downton; Matteo Fogale with Alejandro Canales

The students were Isobel Browne-Wilkinson, a Brighton University second-year, who was paired with ‘nature-first’ furniture maker Sebastian Cox; Central Saint Martins second-year architecture student Alejandro Canales, who was mentored by Uruguayan designer and curator Matteo Fogale; and Emile-Gabrielle Lemaitre-Downton, a product design student at Ravensbourne, who was put with ceramics, carpentry and metalwork specialist Andu Masebo.

The mentors worked with the students over six weeks in September and October last year, steering the development of their design. In addition, participants were provided with materials and a £1,000 stipend.

The students’ designs are all very different. Lemaitre-Downton created a series of side tables constructed with traditional joinery techniques, featuring the patterns and geometries these create. Browne-Wilkinson designed a series of benches that tesselate ‘following the sun’s path’, and Canales repurposed leftover carpet tiles from the interior of the Black & White Building into a saddle chair, inspired by their Texas upbringing – creating the look and feel of a horse. The pieces merge sculpture and furniture together, and the quality is high; you can’t tell that a non-expert has made them.

Source: Ian Tillotson

The furniture pieces made by the students

As a plus, all nine shortlisted students were offered networking opportunities. Waugh Thistleton associate director David Lomax gave a session about sustainability and timber building, while Daytrip offered a tour of its interior design studio. Adams points out that there is a real need for more open chances like this. ‘These students now have something extra in their portfolios and we learnt that this is something that means more to young people than assumed.’

POoR Collective has plans for more programmes like this. ‘We don’t care about one-off initiatives, it’s about longevity, where they’re sustainable,’ Adams adds. ‘A lot of companies assume that when working with young people, the quality of the work is lowered. That isn’t true.’ He highlights the products made by the Mentors & Makers programme. ‘It’s not as if you can tell they are made by students … These are high quality pieces of design.’

Source: Jake Curtis

It's a lovely way to tie the sustainability story of the building together, holistically. In our current drive for ultra-sustainable architecture, with numbers a defining design tool, social sustainability and just thinking about the people at the heart of the project can too often be left by the wayside. Programmes like the Mentors & Makers scheme can be scaled up too, with some investment. And this aspect of the story highlights what a useful project this is as a case study for the industry.

It’s good to build with wood. This project hopefully marks a turning point in the use of engineered timber in the UK, yet we shouldn’t be getting so hyped and excited when a building of this type pops up in central London. It should be the norm.

Sustainability statement

Material optimisation was a key consideration from the outset and the design evolved from the idea of an ‘architecture of sufficiency’. Each component of the building has been designed to be as efficient as possible and almost purely functional.

The design is expressed through the constituent parts, avoiding excess or unnecessary architectural flourishes. The beauty of the completed building stems from the inherent qualities of each layer and each material.

The simplicity of the building belies its groundbreaking innovation. The fully engineered timber structure comprising a beech LVL frame with CLT slabs and core sets a powerful sustainable agenda with only 410 kgCO2e/m2 embodied carbon; a 37 per cent reduction when compared to the carbon impact of an equivalent concrete and steel structure.

Designed for end of life, the structural elements have been bolted together resulting in a fully demountable building which can be reused at the end of its life. The timber structure will act as a carbon store for as long as it is in use, removing a further 227 kg CO2e/m2 carbon from the atmosphere.

The state-of-the-art timber structure is framed by the glazed curtain wall, with solar shading provided by a second skin of vertical timber louvres. A parametric model simulating the movement and impact of sun against the façade determines the layout and form of the louvres, demonstrating how timber, combined with cutting edge digital analysis of environmental performance, can result in a truly 21st-century building.

Andrew Waugh, founding director, Waugh Thistleton Architects

Consultant’s view

The Makers & Mentors programme seeks to provide opportunities for university students studying design-related courses. It aims to not only pair young people with established designers but also help them develop industry-wide skills. At POoR we aim to equip young people with the design tools to create meaningful pieces of art and design but also to help them build their careers.

Working in collaboration with TOG, we were able to give three students an incredible experience that helped build their network and get a better understanding of the professional side of design.

Having nearly 40 applicants for the three spaces shows that there is a real hunger and desire for these types of initiatives.

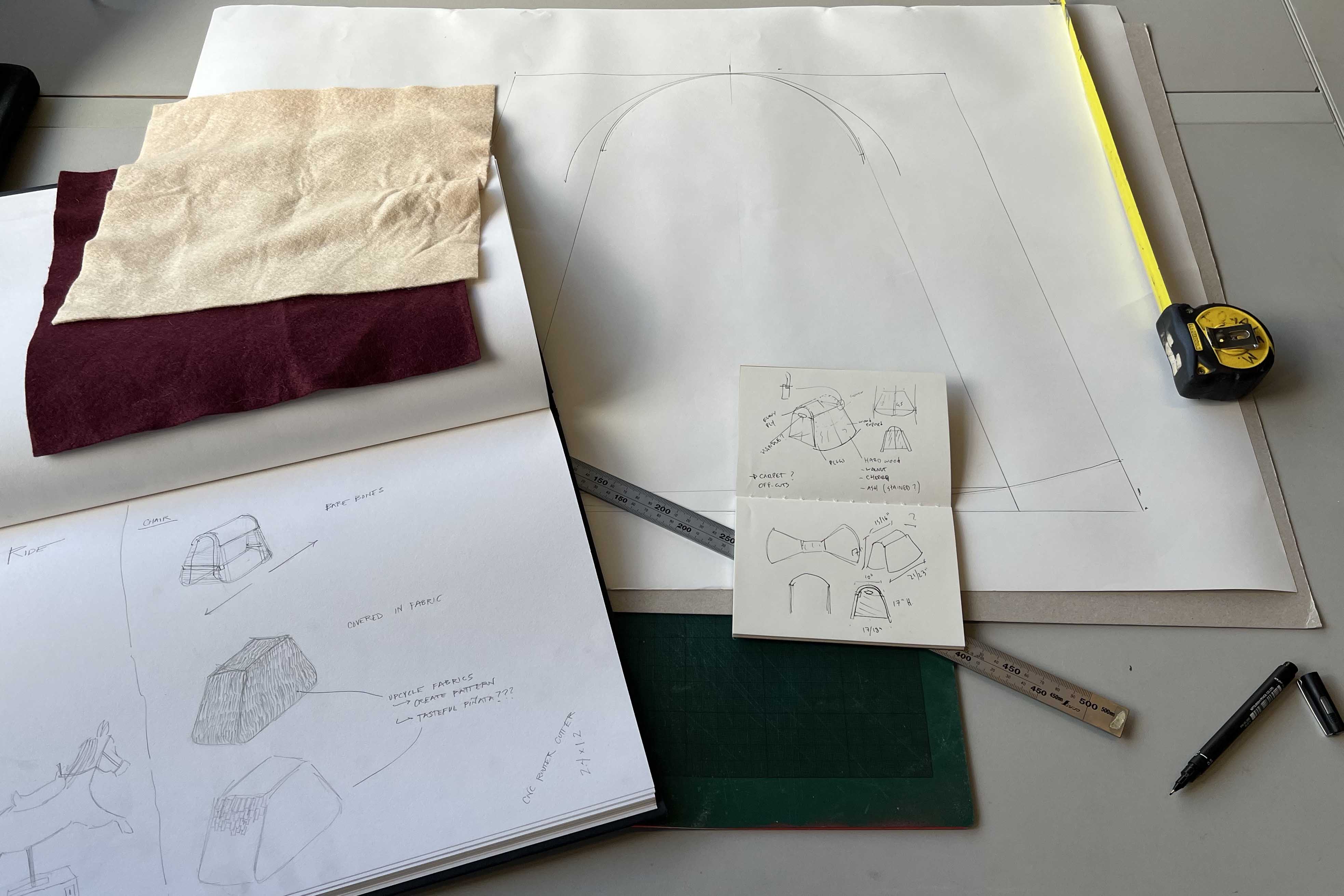

Sketches by Alejandro Canales

If organisations genuinely care about the next generation of designers, then they should be supporting initiatives like Makers & Mentors. This doesn’t only have to be financial; it could be in the form of office tours or seminar sessions similar to those Daytrip Studio and Waugh Thistleton delivered as part of the programme.

TOG was very ambitious and forward-thinking with the Makers & Mentors programme and the end result is something we are all proud of. We hope to roll out more programmes in the future and help further support the next generation of designers.

Shawn Adams, architect, writer, lecturer and co-founder of POoR Collective

Client’s view

Our approach to sustainability for the Black & White Building was wide-ranging, spanning all aspects of the project’s concept, design, build and operation. As our first fully new-build venture, it was an opportunity to realise our vision for the future of office space, where commitment to the natural environment, local industry and social engagement are at the forefront.

There was an existing planning permission on the site already and, in simple terms, our brief to Waugh Thistleton Architects was to design a sustainable alternative that fitted within the massing of the consented scheme. By embracing both the practice’s knowledge and experience in pioneering mass-timber construction, and its innovative approach to the façade design, we could meet our pledge to reduce whole-life carbon – both embodied and operational.

Internally, we collaborated with interior designer Daytrip Studio to create a harmonious environment that, as with all our buildings, strives to optimise client experience through design excellence, while being sympathetic to the building and location. On the Black & White Building, we also had a particular focus on making conscious material choices, sourcing locally and promoting social connectivity. For example, we commissioned local artist Jan Hendzel to create three sculptures for the ground-floor entrance from timber beams we had retained from the former building.

The combined design brief became a celebration of timber, craftsmanship and collaboration. The recurring theme was not solely focused on sustainability, but also on engagement with local designers, makers and artists – including the next generation of young student designers through our Makers & Mentors programme, undertaken with POoR Collective.

We’re proud that this workspace results from the dedication, passion and expertise of all those involved. Ultimately, we hope this project fully showcases the potential of sustainable construction approaches and inspires others to follow in constructing buildings that use responsible methods and materials.

Sophie Werren, lead architect, TOG

Working detail

The building is enclosed in a simple timber/aluminium composite curtain wall system acting as the primary weather seal. The glazed panels span floor to ceiling, punctuated with casement windows allowing passive ventilation. A bespoke spandrel panel in line with the slab encapsulates the compliant elements such as acoustic insulation and fire stops.

While each floor is only 57 per cent glazed, an array of timber fins is layered in front to provide solar shading and minimise operational energy use. Each element is held in place by proprietary stainless-steel brackets and aluminium carriers, designed to be demountable, facilitating maintenance and installation of the curtain wall behind.

The fins are constructed of Tulipwood, a surplus hardwood in the USA, and have been thermally modified, a process that enhances stability and durability while leaving the timber soft enough to be machined. Tulipwood is dark in appearance, a consequence of its 'baking process', greying with age to gain a rich and beautiful patina.

The number and depth of the fins has been meticulously calculated using parametric design to ensure they provide the necessary solar control for each exposure level, dependent on façade orientation and floor height, and that they maximise daylight and views out, while also ensuring material use is optimised in keeping with the design ethos of the superstructure behind.

The building’s aesthetic is derived solely from its functional layers, from internal structure to external shading, exemplifying an ‘architecture of sufficiency’.

Luke Pawlina, associate, Waugh Thistleton Architects

Source: Jake Curtis

The Makers & Mentors programme

Project data

Start on site January 2020

Completion November 2022

Gross internal floor area 4,480m2

Gross (internal + external) floor area 4,906m2

Net internal floor area (base build) 3,652m2

Form of contract Design and build

Construction cost Undisclosed

Architect Waugh Thistleton Architects

Client TOG (The Office Group)

Structural engineer Eckersley O’Callaghan

Structural frame specialist Hybrid Structures

Façade engineer Eckersley O’Callaghan

M&E consultant EEP

Quantity surveyor Gardiner & Theobald

Interior designer Daytrip

Planning consultant DP9

Fire engineer Hoare Lea/Sweco

Landscape consultant SpaceHub

Acoustic consultant Paragon Acoustics/Sweco

Project manager Opera

CDM co-ordinator Sweco

Approved building inspector Sweco

Main contractor MidGroup/Parkeray

CAD software used ArchiCad

Sustainability data

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >2% 29%

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >5% 42%

On-site energy generation 10%

Heating and hot water load 36.66 kWh/m2/yr

Total energy load 53.92 kWh/m2/yr

Carbon emissions (all) 13.6 kgCO2/m2

Annual mains water consumption 0.028 m3/occupant

Airtightness at 50Pa 3 m3/hr/m2

Overall thermal bridging heat transfer coefficient (Y-value) Not supplied

Overall area-weighted U-value 0.8 W/m2K

Embodied carbon as designed 410 kgCO2eq/m2

Predicted design life 60 years

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.