‘It’s the social facility of the area,’ says Agile City co-founder Rob Morrison. We’re at Civic House, a co-working hub, events space and canteen in the north of Glasgow. It’s lunchtime and people are spread across benches outside the building’s simple but unusually painted green and white striped façade, eating vegan food.

Photography: Tiu Makkonen

Inside the cool white cafeteria itself, there are colourful graphic posters pinned up everywhere advertising parties and events taking place at the building during Scotland’s Archifringe festival. The place feels calming despite its proximity to the motorway and canal which divides north and south Glasgow.

Civic House is the second low-budget, high-impact work and event space for Agile City, a non-profit and community interest company, following on from its nearby Glue Factory, and one of a few that have popped up across the city in recent years. It’s also a testbed for modest adaptive reuse, demonstrating carbon reduction innovation without any major ‘built’ architectural interventions. Its architect, Collective Architecture, describes it as Scotland’s first ‘PassivWareHaus’.

Advertisement

Agile City operates as a social enterprise and has two primary revenue streams: renting out workspace and hiring out space for events, including weddings and music nights. Any profit is reinvested into improving facilities and delivering events or projects. All its work is rooted locally around the Forth & Clyde Canal, with the reinvestment cycle aiming to have a positive impact on the local economy and the area’s regeneration.

The refurbishment of Civic House started in 2019. The building was formerly a printing works for left-wing publisher Civic Press, a survivor of radical activity characteristic of early 20th-century Glasgow. Election posters, leaflets and placards were all created here.

Historic photo of Civic Press

The original building – of rendered brick – had many windows across its façade to facilitate the hand composition of type, and had been surrounded by tenements. These were cleared in the late 1960s, along with the local population and industries, as part of an accelerated slum clearance to construct the M8 motorway (see image below) in a dramatic remodelling of the area’s urban fabric. It led to the building being seen as it is seen today: isolated among tall wildflowers. It also marked the point when Glasgow turned its back on the north of the city.

Civic House was left abandoned for years before being acquired by Agile City in 2017. Using funding from the Scottish Government Regeneration Capital Grant Fund, the organisation began internal refurbishment work to convert the building. Internal partitions were stripped out to provide an open-plan studio for events, while overgrown grass and bushes were cleared from the site, creating clear public access.

Photography: Tiu Makkonen

The project from that moment became an iterative process defined by funding. ‘We had to look at the big picture,’ says Collective architect and Passivhaus designer Emily Ong, describing the step-by-step process whereby as capital came in for Agile City, it was able to commence the next stage of works.

Advertisement

Collective was appointed in 2017 to facilitate an energy analysis and feasibility study, defining the scope of retrofitting the building to stringent EnerPhit standards. Necessary energy-efficient improvement works were identified through site investigation work, while building models were developed using PHPP to determine the most appropriate and effective measures and to prioritise these.

Photography: Tiu Makkonen

The ground-floor canteen was the first intervention, intended ‘to bring people together’, says Morrison. Given its industrial surroundings, there was nowhere for nearby organisations and residents to meet, eat lunch, exchange ideas or just socialise. The canteen and events space fed into Glasgow City Council’s cultural agenda for bringing people to the area, and was also used to test Agile City’s business model by hiring out the space at night for parties.

The building was also temporarily used as studio space for dispersed Mackintosh architecture students following the 2018 fire. The first major phase of the project was a roof upgrade in 2019. The previously dilapidated leaky slate roof was replaced with a thermally efficient and airtight insulating composite metal version, also laying the ‘roofwork’ for a 50kW PV array.

New Typologies exhibition for Scotland's Archifringe at Civic House in 2017. Photography: Robb Mcrae

Phase two included the installation of PVs in March 2020 with completion of external fabric efficiency works (airtightness and insulation), installation of high-performance windows and doors, and an MVHR. Agile City’s wider list of works includes installing an air-source heat pump, upgrading all lighting to LEDs enhanced by motion sensors, aerated taps and Wi-Fi-enabled thermostat controls to create zones responsive to different types and volume of use.

Air pressure and smoke testing was carried out to identify air leakage at key stages. This intentionally preceded external wall insulation works as Collective wanted to investigate the permeability of the external walls so they could be upgraded to the best performance possible.

Collective learned lessons from its work on Woodside, a high performing upgrade of three 1960s towers on the periphery of the city, completed in 2019. This was intended to be Passivhaus but fell short due to its contractor not being trained in the approach. For Civic House, the roof and external works were subcontracted, inhouse, to local organisations. ‘The project ended up being about different components and organising between different trades,’ says Ong. Morrison adds: ‘There was fluidity between the role of architect, client and different subcontractors.’

Both Morrison and Ong agree that the overlap worked to everyone’s benefit with everyone learning from each other. A lot of education on EnerPhit, particularly on airtightness, was given to contractor AFS, with one example highlighted by both: cold bridges in the downpipes. ‘It is all about including them in the conversations,’ says Ong. ‘They started taking pride in it.’

Photography: Andrew Lee

The most aesthetic move in this retrofit was Collective’s elevational treatment. Historically, the front elevation was predominantly painted brick with feature panels between windows expressed in wet dash render. It was collectively decided that to reinstate its historic features would be a pastiche of the original. Instead, the design seeks to build on its original industrial form and enhance the dominant features of massing, rhythm and repetition.

The main connected entrance block has been retained in scale, renewing the feature panels of deep aggregate between windows. New PPC aluminium windowsills connect across these panels in reference to the original. The entrance door reveal is now expressed in a vibrant red, while recessed window panels between white bays are reinstated in a dark green and finished with clear retro typography.

The striped effect is simple yet stands out and certainly diverges from its original form, reinforcing the industrial shed-like nature of its typology. Perhaps, though, the external colour palette could have been braver. The white and green doesn’t somehow advocate for its exciting programme within: architecture, design, food, film and music.

Agile City is keyed in with its end-users, and retrofit is context dependent. Its other project, Glue Factory, double the size of Civic House and with a very different structure, is adopting a more localised thermal strategy while Civic House is ‘all about the envelope being efficient’, says Morrison. With Glue Factory, heating is rolled out ‘like a hospital drip’, he laughs.

Photography: Patrick Jameson

Inside Civic House, a lot of its modest finishes have been left rough and ready. Downstairs in the canteen and events space, the furniture is relatively makeshift but hardwearing, an indicator of where money has been prioritised. It’s a work in progress and Morrison reiterates the project’s phased development model: when they have money to spend, they spend it the best they can.

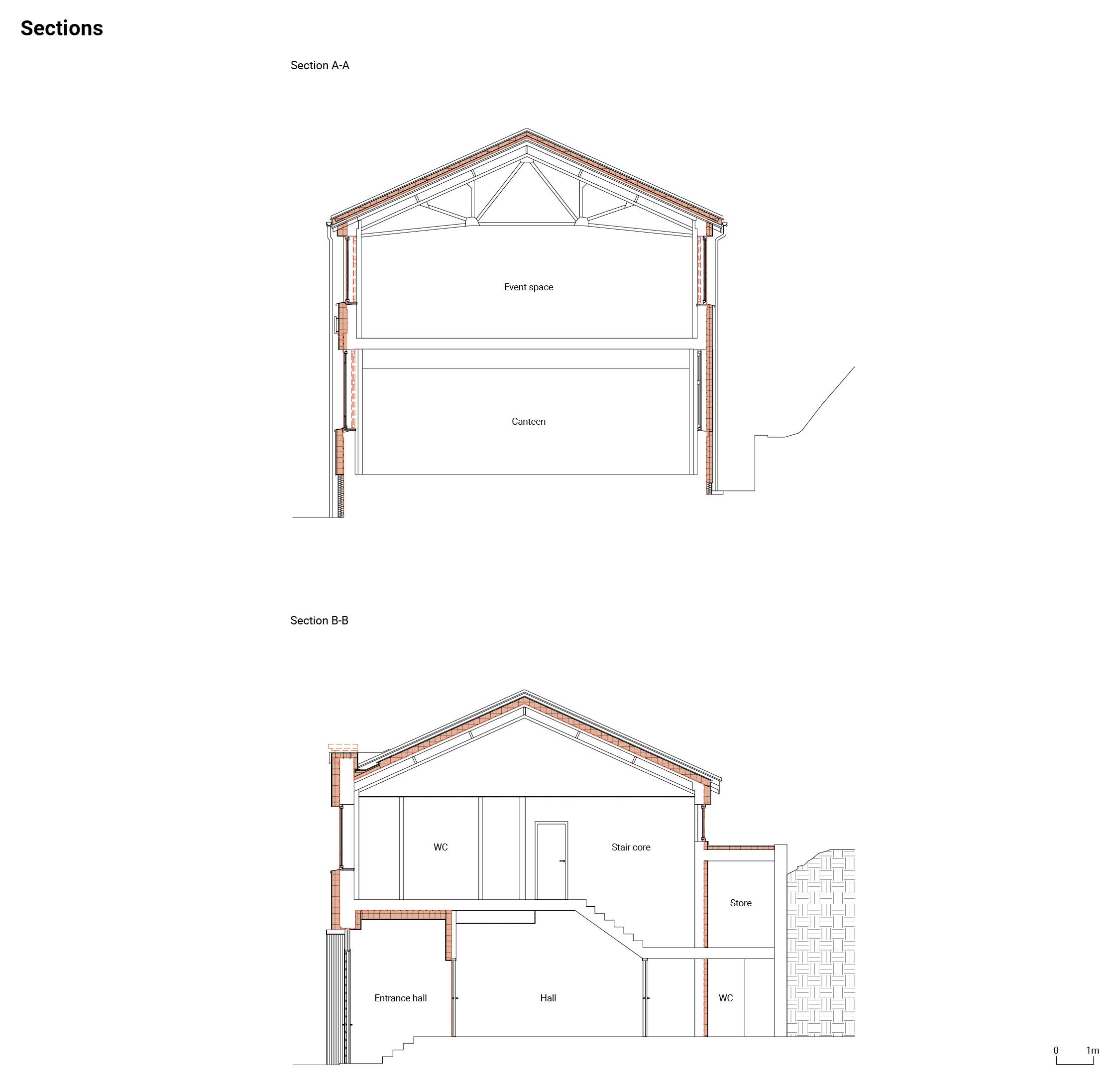

In the upstairs, now a co-working space with subsidised rent, the ceiling and walls have been stripped back to express a beautiful timber roof structure with slender metal trusses and exposed brick, creating a light airy, warehouse space. The high-performance windows and MVHR make it incredibly quiet with a consistent temperature, despite abundant windows. The worn timber floor has been replaced with hardwearing parquet and there’s a glazed partition with mustard curtains dividing the workspace. ‘We tried to keep the construction as honest as possible,’ says Morrison.

Photography: Collective Architecture

After lunch, he walks us up to the canal, which is at the same height as Civic House’s roof. After passing a DIY community skatepark in the relics of another building, Hoskins’ 2016 headquarters for the National Theatre of Scotland comes into view, relocated to Speirs Wharf in an attempt to fuel the regeneration of this previously neglected area into a cultural quarter. But it’s not the large projects that are fuelling change, it’s the smaller, grassroots organisations like Agile City, making tiny but important incremental steps.

Events at Civic House

‘Our work is about repurposing spaces,’ says Morrison. After emerging from an architecture degree at Glasgow School of Art during the recession, he co-founded Agile City. The organisation ran events and the Test Unit series of design and architecture summer schools exploring approaches to city development, particularly using Glasgow’s empty buildings – including Civic House. It then moved on to acquiring existing buildings itself and is now a catalyst for change, playing a small part in the ongoing regeneration of the area around the canal.

Only £450,000 has been spent so far on upgrading Civic House. It was one of many vacant buildings across the city following industrial decline. It now sets a precedent for showcasing a process of development that is less capital intensive, more energy efficient and quicker to respond to people and change.

Architect’s view

Prior to the retrofit works on Civic House, the building was cold, draughty, and poorly ventilated. Our vision was to create Scotland's first retrofit ‘PassivWareHaus’ — an exemplary model of carbon reduction innovation. By repurposing Civic House, a century-old industrial structure, we want to demonstrate that, by taking a longer-term strategic view, it is possible to renovate existing building stock up to modern building standards. We took advantage of the east-west orientation and existing glazing patterns, carefully planning the retrofit to preserve and enhance the building’s unique features while ensuring a comfortable indoor environment for occupants, whether it served as a co-working space or hosted events for up to 200 people.

To define the long-term energy goal, we suggested taking a fabric-first approach, focusing on external works to reduce the energy demand and associated carbon emissions, using the EnerPHit standards as a design tool. The comprehensive ‘whole systems approach’ included external wall insulation, high-performance doors and windows, an MVHR system, an air source heat pump, composite insulated roof panels and a 50kWp PV roof array.

We closely collaborated with the client to develop a phased retrofit plan aligned with available funding. This reflective and incremental process is ideal for community-based organisations and those adopting a staged approach to their retrofit projects.

Now complete, the project aims to deliver a public learning programme that explores sustainability and inclusive urban development, fostering knowledge, skills and local behavioural change. As a community-based workspace, the project aims to demonstrate that small actions can generate large-scale impact.

Emily Ong, architect and Passivhaus designer, Collective Architecture

Client’s view

Agile City is a community interest company based in Speirs Locks, north Glasgow. We run two buildings – Civic House and Glue Factory – creating work and event space for architecture, design, making, food, film and music. Our work is deeply rooted within our local context: a post-industrial area next to the Forth & Clyde Canal.

As a social enterprise, one of our core objectives is to initiate ambitious projects that test how buildings are produced in more equitable ways and contribute to the regeneration of our local area.

The design, development and running of our spaces is an incremental process: testing the building with our community of users and continually learning how we can make improvements. This process has been at the core of Civic House – a phased development that would create a prototype of how to retrofit a former industrial building to become energy positive.

In 2018, we commissioned Collective Architecture to carry out a feasibility study for a phased development that would allow works to be delivered as different pots of funding became available. This kick-started the project, which is now 90 per cent complete. There has been a vast amount of learning around co-ordinating contractors, organisational capacity and how we would do things differently.

Civic House demonstrates that not-for-profit local organisations have the power not only to save much-loved buildings and bring new life to post-industrial districts but also to become small-scale sustainable energy generators. The building is already fulfilling its purpose as a micro power station. During the 12 months from January 2022, it used just 1,684kWh of gas and 9,706kWh of electricity, while generating 30,780kWh of electricity – equating to a net energy gain of 19,390 kWh.

Rob Morrison, co-founder, Agile City

Engineer’s view

Design Engineering Workshop was consulting structural engineer on the Civic House project. We were involved with various alterations to the existing building. The key elements for us were to deliver a cost-effective structural solution that delivered the client’s brief and vision. We tried to adopt a light-touch approach and worked closely with client and architect to understand the requirements. We spent a lot of time understanding the existing structure. This allowed us to add roof insulation and finishes without strengthening the original steel roof trusses. This approach fed down to even the smaller elements, such as builders’ work holes for services. We were able to work with the team to arrange the opening locations so that no strengthening works were required, keeping costs to a minimum and protecting the original building.

It was the collaboration that really helped deliver the right solutions. This is highlighted with the new wall breaking up the main space. It was to be as light a structure as possible with timber. The client worked extremely hard to source the right timber and we were then able to check the design and agree fixings centres. There was constant dialogue with the client for all elements on the project. For us, this project is about bringing life into the building and protecting it rather than big structural intrusions. It might not appear that much structural work has gone on but we have worked hard to design out any unnecessary engineering.

Mark Sinclair, director, Design Engineering Workshop

Working detail

The energy retrofit for the Civic House project was undertaken with a clear design intention: to improve the building’s thermal performance and address water ingress issues resulting from a lack of historic maintenance.

The StoTherm external wall insulation (EWI) system was selected as the optimal and durable solution, using silicone-rendered EWI with EPS insulation boards securely adhered to the substrate.

A key aspect of the retrofit project was the meticulous approach taken towards window installation. The window frames were pushed all the way into the EWI, and fixed to an 18mm plywood window surround, which was then secured back to the masonry wall. The positioning of the windows was carefully planned to align with the external insulation.

This approach effectively ‘wrapped’ a portion of the frame in insulation, further reducing heat loss and improving energy efficiency. The dilapidated slate roof has also been replaced with a thermally efficient and airtight insulating composite metal roof with U-Value improved from 2.87 W/m2K to 0.1 W/m2K.

To ensure effective airtight seals throughout the building, high-quality proprietary airtightness tapes and liquid membrane were used. These were installed behind the EWI insulation, covering the connections between the roof and walls, the window-to-masonry/render junctions, historic vents, and stone and concrete projections.

We meticulously managed any necessary penetrations through the existing brick wall by sleeving PVC pipes and filling them with spray foam insulation. Roflex airtight grommets were used for airtight sealing around the pipes.

These measures have significantly optimised the building envelope, reduced energy consumption, and contributed to an energy-efficient design.

Emily Ong, architect and Passivhaus designer, Collective Architecture

Project data

Start on site: December 2020

Completion: October 2022

Gross internal floor area: 839m2

Construction cost: £450,000

Construction cost per m2: £536

Architect: Collective Architecture

Client: Agile City

Structural engineer: Design Engineering Workshop

Quantity surveyor: Martin Aitken Associates

Principal designer: Martin Aitken Associates

Approved building inspector: Glasgow City Council

MVHR designer: Paul Heat Recovery

Graphics: Risotto Studio

Interior design: Agile City

Passivhaus designer: Collective Architecture

Main contractor: AFS (Scotland)

CAD software used: Revit

Annual CO2 emissions: 2.47 kgCO2/m2 (for operational carbon only in 2022, based on UK grid carbon of 0.155 kg of CO2e per kWh of electricity and 0.183 kg per kWh of gas)

Photography: Patrick Jameson

Sustainability data

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >2%/>5%: Not calculated

On-site energy generation: 30,780 kWh/yr

Heating and hot water load (actual): 10.85 kWh/m2/yr

Total energy load (actual): 15.5 kWh/m2/yr

Carbon emissions (all): 2.47 kgCO2/m2 (based on operational energy)

Annual mains water consumption: 477 m3/yr (April 2022-March 2023)

Airtightness at 50Pa: 1.70 m3/hr/m2

Overall thermal bridging heat transfer coefficient (Y value): 0.10 W/m2K

Overall area-weighted U-value: 0.15 W/m2K (excluding floor)

Embodied / whole-life carbon: Not calculated

Predicted design life: 60+ years

Total in-use energy consumption for 2022 is 15.5 kWh/m2/yr. Assuming 70% of this is from space heating and hot water, the heating and hot water load is 10.85 kWh/m2/yr. Note that this data is acquired from both gas and electricity metering, which includes energy offset from PV generation.

January-December 2022

Gas metering: 1,684 kWh

Electricity metering: 9,706 kWh

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.